Draw Every Line.

The drawing board was an extension of my mind in architecture school.

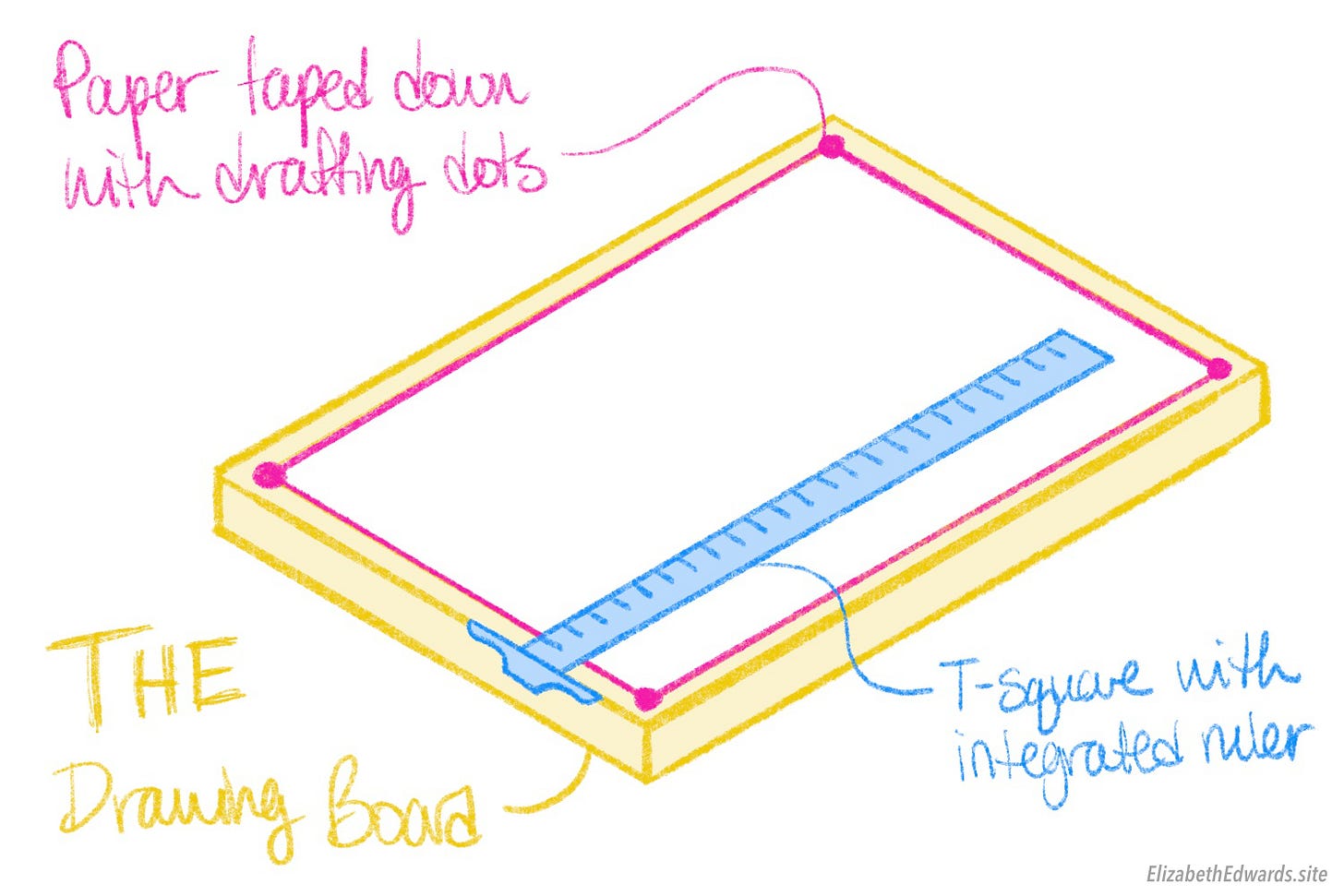

I’d shove my t-square against the straight edge of my drawing board, and lay the sharpened point of a 4B pencil on the paper at the one-and-three-quarter-inch mark. I’d glide that sharpened point from left to right, within the crevasse between the t-square and paper, while rotating the pencil with my thumb, before stopping at the five-and-one-quarter-inch mark. The thickness of the line was perfectly even.

This line represented the edge of a wall.

Once that line is drawn, there’s no going back. That shiny dark graphite would leave a finely dented trough in the paper where the line once lived. So I’d have to measure, cut, lay down a whole new sheet of paper, and start my drawing over again. It was already midnight. No thank you.

I’d then shift my t-square down to draw the next line.

Maybe to you this process sounds slow, tedious, and repetitive, but learning how to draft architectural drawings by hand (almost 15 years ago) was one of my greatest life lessons.

Every line was intentional and represented something, like a wall, or a floor, or a low ceiling above. The line didn’t draw itself. I brought it into existence, which means I had to think about what that line really was. When I finished drawing, all the lines, together, became a composition that represented a building I designed.

These lines represented me and my ability to think in 3D.

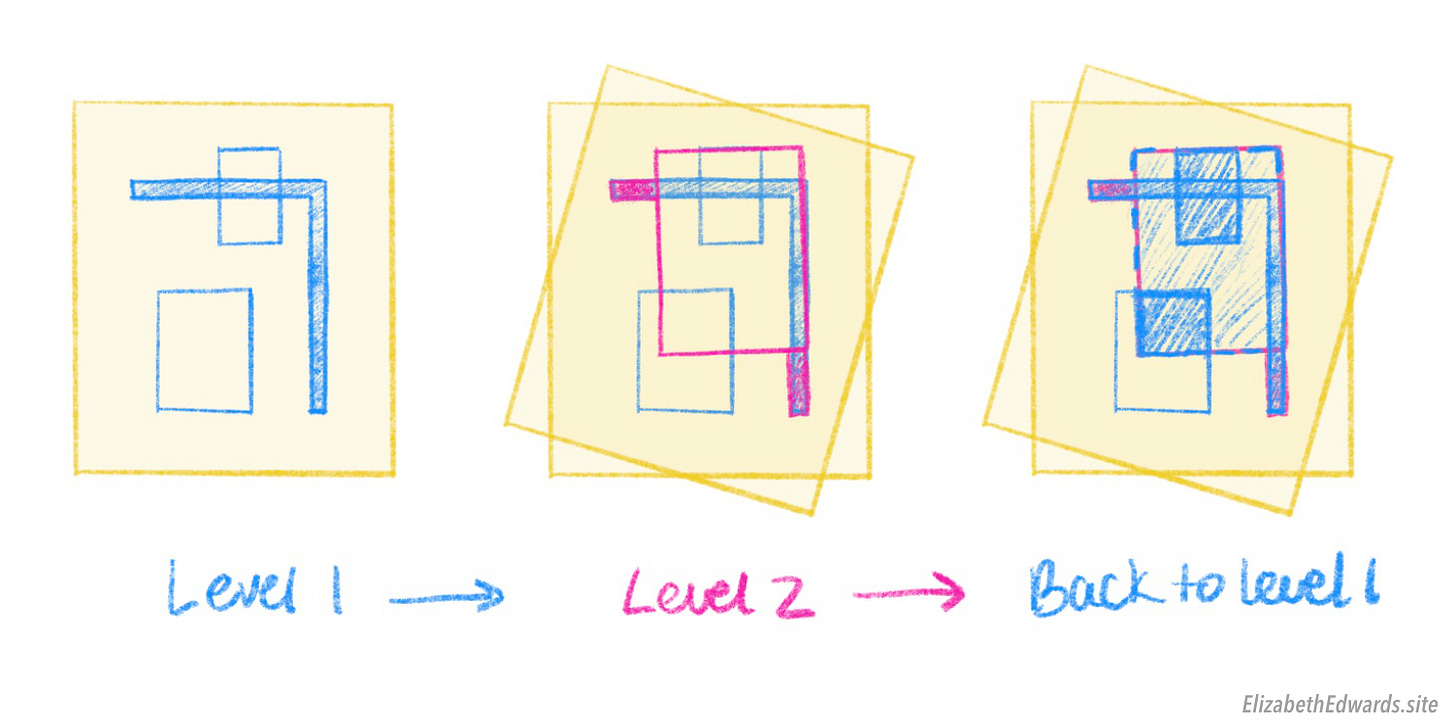

Every wall, floor, ceiling, and room was ingrained in my memory. I’d draw a plan of one floor on tracing paper, then lay down another sheet of tracing paper and draw the next floor on top of it. I’d continue this process going up or down the building.

This method of overlaying the drawing of each floor showed me the relationships I was making between rooms and floors, three-dimensionally. I would always discover relationships that didn’t make sense, so I’d find myself redrawing floor after floor, over and over again.

This process was not easy. But after five years of obsession, rigor, and sleepless nights, I finally built a mind to hand connection. By learning to draw by hand in three dimensions, I learned how to think in three dimensions. This is the most important skill an architect needs, and I fear that this fundamental lesson is being lost in architecture schools today.

A few months ago, I was invited to a mid-crit, to give feedback to third-year architecture students at the local university. These students spent half a semester designing a community center in Queens. Instead of a midterm exam, architecture students present their design progress for feedback, not only to their professor and classmates but also guest architects. Through this process they learn how to talk about their work. But more importantly, they learn if their drawings show their ability to think in 3D.

When I was in school, mid-crit was a special day. Every wall in every classroom and hallway was completely covered, floor to ceiling, with hand-drawn drawings of different sizes and shapes. Some looked like detailed construction blueprints, drawn in ink on a frosty plastic-y paper, while others were a series of small 3D pencil scribbles on trace paper, colored in with a rainbow of highlighter arrows to show off different features, like how people move through the building, or denoting public versus private staff spaces.

I’d walk around and see everyone’s work, but always tripping over the three dimensional hand-made paper models that covered the floor. Most were made of cardboard, hacked together with tape and hot glue, and looked like they were cut with our own teeth. Some were covered in blood because we’d work on them at 2 AM, exhausted but pushing through, and the utility knife in our hands occasionally slipped in the process (oops!).

Mid-crit was the time to show everything I had. There was no holding back. The more drawings I had to show, to prove my design process to my professor and classmates, the better. It’d be easier for anyone to see holes in my work, which I wanted others to discover, so I could resolve them.

But at this mid-crit a few months ago, there was no process work. There were no hand sketches and no drawings pinned up on the walls. Instead, I sat for 5 hours, watching students flip through their sleek and soulless powerpoint slides projected onto beat up and over-painted pin-up walls in a dimly lit room. The students presented their computer generated floor plans, which were a random arrangement of various sized rectangles. Whenever I’d ask why they drew that hallway wider than their auditorium, they’d silently stare back at me, clueless.

What happened?

These students started architecture school during the pandemic in 2020. Due to lock-down mandates in NYC, they had to work independently from home. They did not learn how to draw by hand, or even sketch in a sketchbook. They immediately jumped into working within 3D modeling software.

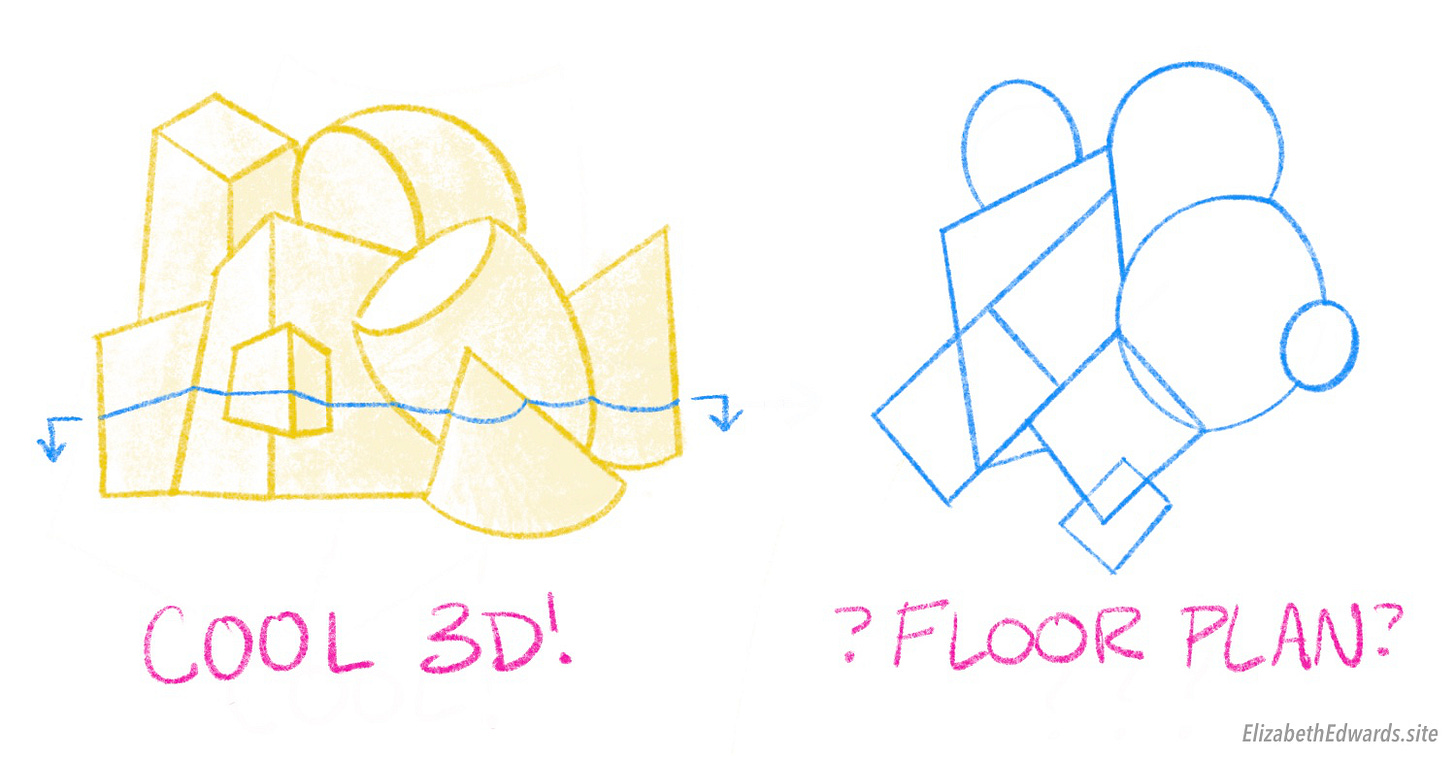

These students modeled forms that looked cool, and used that to automatically generate their floor plan drawings. They did not draw through each line. As a result, they often had no idea what was inside their building. They had too many awkwardly shaped rooms, with sharp triangular corners that no one could reach. And not only were these students unable to solve these conflicts, but they were not even aware they existed.

The software isn’t the culprit here. I learned these 3D modeling softwares, but only after learning the fundamentals of design through hand drawing. When I was a student, I watched some of my friends jump right into 3D software in an attempt to not only skip the tedious hand-drawing process, but the design process as well. Sure, some of the 3D imagery they made looked cool, but that’s all it was, a cool image, that overcompensated for awkward rooms within it.

There’s too big a trend today to automate ALL tedious tasks with software for the sake of efficiency. And this trend is affecting today’s architecture students. These students are not slowing down, taking their time, and learning the value of drawing line by line. They’re fixated on the software so they can design faster and appear more desirable when looking for jobs once they graduate. But they don’t realize they’re selling themselves short. They can’t justify the design decisions they make, and they can’t think in three dimensions. They need to be able to do this to become an independent architect. No client wants to pay millions of dollars for a building with rooms they can’t use, or access, because of an awkward triangular shaped corner.

They’re learning the architects’ software, at the expense of learning how to think like an architect.

Don’t be lazy. Draw every line.

Thanks for reading! If you like this essay, and want to read more, subscribe below: